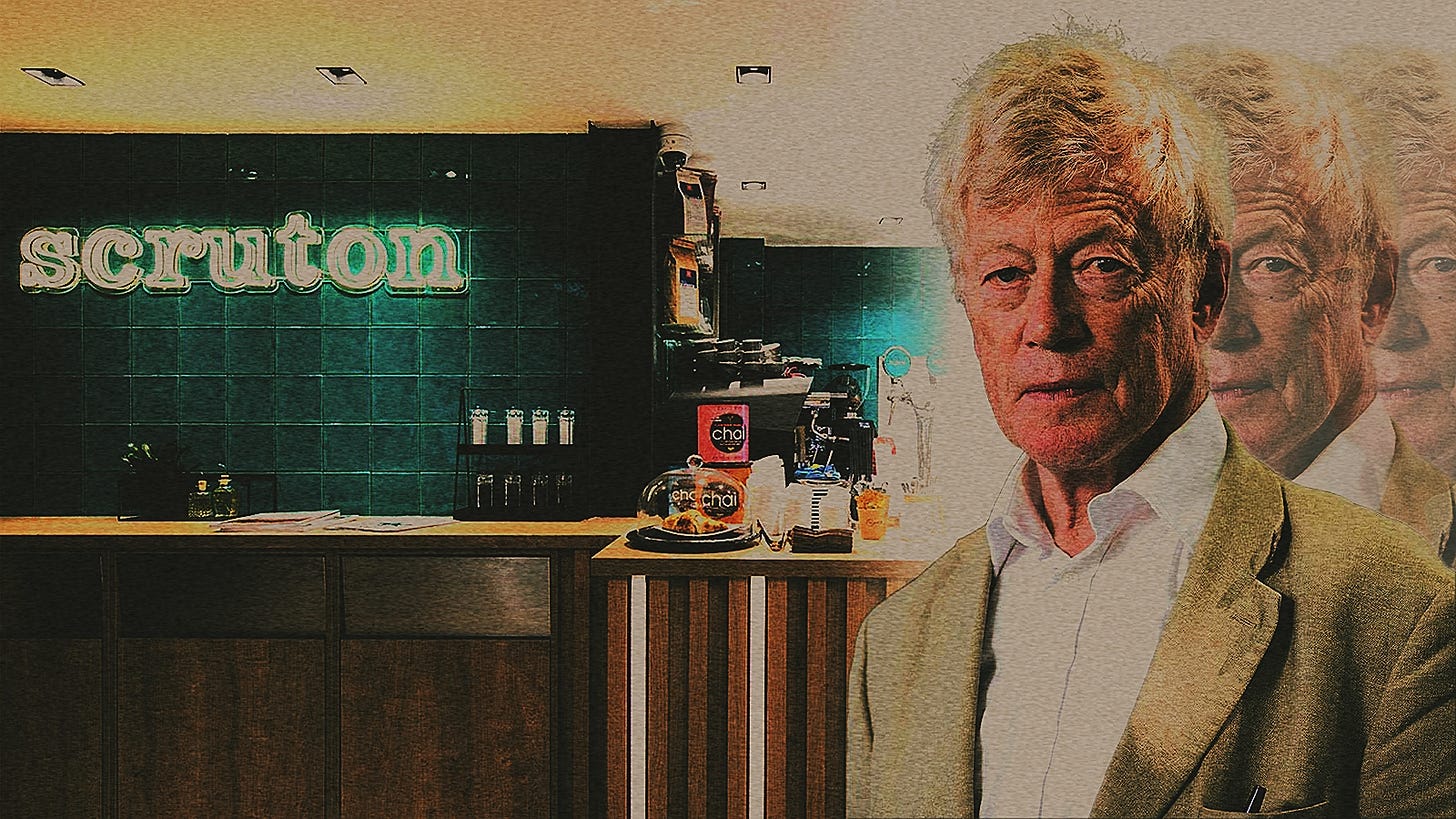

The two words, “Scruton Café,” are meaningless to most people. In all probability, they do not know who Roger Scruton, traditionalist conservative philosopher par excellence, is—and this is understandable. The skies are polluted. If we are to glimpse the stars, we must climb high peaks. But for those of us who have found ourselves crowded onto such peaks, voyeuristically angling for a glimpse, those two words, echoing from crag to crag, issuing ostensibly from some unseen yodeler, command our attention. In their interstitial blank space, their concatenating silence, we sense a tryst between sacred and profane: a mysterium tremendum et fascinans.

But the Scruton Café is not merely a phrase meant to evoke wonder. It’s a real place and in no way does its reality weaken our fascination. Apparently, it’s even located in the far-off, fairytale land of Hungary where if certain personalities are to be believed, great things are being done and greater (formerly fringe) intellectual movements are being feted at State-expense.1 Moreover, when the Scruton Café first opened its doors, the good news was heralded to anglophone twitter via a range of articles in popular right-leaning outlets.

In National Review, John O’Sullivan gave readers a glowing account of the new café and speculated wishfully about an American counterpart. In The Critic, Tibor Fischer described how though having a café launched in a person’s memory is not quite an honor on par with deification, that he was nonetheless “touched.” In The American Conservative, Rod Dreher, with estimable panache, confessed in one post to having his coffee at home from a cup he’d “swiped from Scruton.” And later, in IM-1776, in celebration of the café’s anniversary, Ben Sixsmith offered a highly readable Stoppard-esque account (which I have no reason to believe is fictional) of visiting the café, wherein “smartly dressed” patrons answer his questions with reverential Scrutonisms, and whereafter he encounters mid shadows “flitting about the dusk” a shade resembling the café’s namesake, who, drinking a glass of wine and lighting a cigar, assures him, “I’ve earned this.”

For the most part, these articles note a few things in common about the new café: it’s a few blocks from Hungary’s parliament, it’s full of Roger Scruton’s knickknacks (e.g., some of his records, his old-timey gramophone, and one of his teapots), and jarringly that the whole café has a sort of, in Sixsmith’s words, “glossy bourgeois hipster vibe”—the likes of which Scruton excoriated throughout his whole career as an advocate of traditionalist aesthetics. A google review of the café describes the establishment as boasting, “bean bag seating,” “vegetarian side dishes,” and a “vegan cake option.”

But before we go on to try and broach the mystery of the Scruton Café, I ought to note that, outside of anglophone-twitter-discourse, the café that precipitated all those pieces does not actually go by that name, and that there are now not one, but three “Scruton Cafés”: “Scruton BELVÁROS,” “Scruton V.P.,” and “Scruton MCC.”

However, this great revelation I have just made to you—i.e., that the café’ is actually eponymous with Scruton and that it has become a rapidly expanding chain ostensibly doing good business—should not give you the confidence to conclude the thing of mystery I have thus far been describing is in actuality nothing more than an otherwise commercial café chain trading on Scruton’s reputation as a political activist in Cold War Europe (or in O’Sullivan’s words, “an intellectual Scarlet Pimpernel”). His possessions were not bought as an investment at auction, but were donated by Scruton’s widow. Copies of Scruton’s books are available for sale at every location and are featured on the chain’s website. Moreover, shortly after its opening, the café’s basement hosted a discussion of Scruton’s life and philosophy with Douglas Murray, O’Sullivan, and Ferenc Horcher. And that event wasn’t even a one-off. A glance at the Café’s schedule yields upcoming programs on the impact of reading, a round table on the current situation of church higher educational institutions, and a salon evening featuring works by Telemann performed by the Simplicissimus Ensemble on period instruments.

But then again, lest you feel too reassured that the Scruton Café is a respectful monument to our strawberry blond Pimpernel’s posterity, consider that on the very same schedule there are singles events for young adults aged 25 to 35, Rockabilly Nights, and New-Agey fairy tale therapy workshops—which is to say that at every turn the Scruton Café, true to the name by which it first echoed through the Olympian peaks of niche-right-leaning-Twitter, seems to still be a sort of contradiction.

But compounding the aura of this mystery, there is a strange marvel: some people, including those who ought to be familiar with Scruton and his aesthetic sensibilities, such as O’Sullivan, do not find the café contradictory at all. In his National Review piece on the café, O’Sullivan even goes so far as to suggest the café’s slogan should be “For those who like Coffee and Conservatism undiluted.”

How? For what strange reason did O’Sullivan surmise that not only is the Scruton Café not an instance of disconcerting inharmoniousness, but more than that a thing of purity—a thing in which there is manifest “Conservatism undiluted”? Now, an ungenerous peak-dweller might look down and peremptorily mark him as a fool, but we here are not ungenerous. Perhaps O’Sullivan has simply gone mad. And if that’s so—then so be it. The ancients held the mad and their utterances to be sacred. We shall do no less. (Of course, there is a possibility O’Sullivan’s wiser in saying this than we know.) In any case, what right do we have to go about calling a mystery impure?

But what is this mysterious thing? And I do mean “thing” in the singular. Though there are multiple Scruton Cafés, what concerns us is not any one of its instances, but that which it presents to us. Every Scruton Café is, to borrow the transcendentalist phrasings of Captain Ahab, but a pasteboard mask behind which something undoubtedly puts forth the mouldings of its features. Yea, as Moby Dick would severally breach in the waters of Good Hope, the Sulu Sea, and the Bengal Bay, the Scruton Café appears to us in three, convenient Budapest-location. It tasks us, heaps us, &c. But if it is but a pasteboard mask, does it not surely conceal Scruton himself?

That is to say, who is Roger Scruton? Certainly, we all know one side of him: philosopher, critic, columnist, publisher, editor, novelist, knight, wine connoisseur, foxhunter,2 dissident, medalist, composer, culture critic, and so on. This is the side that shines forth for our admiration. When we regard it from the peaks, it beckons us ever higher and when we fall, it lights our way back up. But like heaven’s most romantic luminary, Scruton has another side, the substance of which, though less beguiling, served to keep his being dangling in the ether for our edification.

It is this second side whose shadow we see in Scruton’s somewhat self-promotional Scrutopia Summer schools, association with a graduate program with leisurely (if not gentlemanly) course requirements, fellowships gilding the reputations of otherwise quotidian policy shops, and his much-maligned public relations ventures undertaken under the aegis of his Horsell's Farm Enterprises with Japan Tobacco International.

Of course, this latter side does not negate or somehow diminish the first; no romantic could bear to love only half the moon. Moreover, practically speaking, the intellectual who does not begin with means or marry into them often lives with the brilliance of his or her purity till about 29 and then dies with it in the gutter.3 That Scruton lived till a good old age demonstrates his acumen at squaring the circle of intellectual life within the angular confines of the city.

But then again, he did not simply live in the city. It’s is one thing to eke out a living as an academic and write the occasional book, and quite another to be the posterchild of traditionalist life while fully engaging in postmodernity to the extent the business set up on your farm also functions as a public relations firm with international corporate clients.

Yes, like the Scruton Café, the mystery of Scruton himself is enwrapped in contraries. To a degree, he is reminiscent of one of his influences, Edmund Burke, at once a great defender of tradition whiles also being a great defender of the then newish and widely despised notion of free trade—which would eventually, for better or worse, erode the very traditions he so loved.4 But of course, Burke never lived long enough to see our world. Would he be as he was if he were alive now? Would he be comfortable in our world—or, even, the Scruton Café?

In any case, because the comparison to Burke really only holds on an intellectual level and does not quite make the same sense in the realm of spirit—in which our mystery like all mysteries dwells, there is a more tantalizing comparison to be made that takes into account Scruton’s character as a romantic, firebrand, wary (though careful) reader of Hegel, and a writer of opera. That is, if you haven’t already guessed—there is a comparison to be made between Scruton and Richard Wagner. And lest this comparison seem wholly out of pocket, consider that one of Scruton’s students, Paul Krause, (editor of VoeglinView), in discussing his teacher’s works on the latter, makes it himself, describing them as “a match made in heaven, or hell, depending on your perspective and appreciation of irony.”

There is ample reason to believe this based on Scruton’s own writing on Wagner, particularly his “Wagner trilogy”: Death-Devoted Heart: Sex and the Sacred in Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, The Ring of Truth: The Wisdom of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, and Wagner’s Parsifal: The Music of Redemption (the last of which he had been working on in the season leading up to his death and which was posthumously published in the summer of 2020.)

Per Krause, in Scruton’s discussion of The Ring, we find an all-out champion of Eros. He preaches of the vanity of a cold and austere Valhalla that must be renounced in pursuit of love. He parts the curtains and presents Wagner’s Brünnhilde renouncing her divinity for Siegfried. Despite betrayal, before riding off into an immolating fire, she cries out at the last, “Siegfried! Siegfried! Sieh! Selig grüßst dich dein Weib!” which does not flow very naturally in English translation, but denotes to the audience that in spite of everything she is going to die unto Siegfried in a state of holy ecstasy.

To renounce the promise of bloodless abstractions for a thing existing in a time and place, to prefer the mortal that tastes of death to the immortal that never will, to die for love of a creature of the flesh who must eat and drink to live—all this and more do we learn from Scruton’s later works. Indeed, the Scruton Café sells Scruton’s books and it sells coffee, but it is not a bookshop. To understand what Scruton understood is perhaps to see that there’s nothing dishonorable in this.

But then again, patrons of the Scruton Café are not ecstatically immolated in romantic fire. At its warmest, the Scruton Café is little more than cozy. And yet—in spite of all this discussion—in the depths of this coziness there remains the café’s mystery and entailed therein that of its namesake and his legacy.

To that end, of all the things published in the wake of Scruton’s passing, the most poignant was perhaps written by the Reverend Steve Wilkinson of All Saints’, Garsdon, where Scruton played the organ.5 He wrote two things that have stuck with me all these years: “Even as he went through chemotherapy in the past few months, my offers of visiting for prayer were politely declined; I now understand that he never considered death to be a possibility until his very last days” and “He would regularly play the organ for us at All Saints’, Garsdon, and would usually arrive without fanfare but with barely two minutes to go to the start of the service, and, afterwards, he would disappear just as quickly.” Taken together, these statements paint a picture of the sort of man whose legacy was fated to be as we find it. How could anyone not yearn to know his secret?

Yes, how is it that the most tangible monument to Scruton’s legacy is a café chain in Budapest that hosts Rockabilly nights? When Saul was in a tight spot, having exhausted other avenues of inquiry, he infamously sought out the Witch of Endor to call up his wise friend from beyond the grave so that he could pose his question directly. Against my better judgement and Saul’s example, I am tempted to do likewise. But then again Sixsmith has already dealt with Scruton’s ghost. Thus, I hesitate, and also, if not sinful, it would certainly be rude to bother him again. After all, concerning the Scruton Café, he has said per Sixsmith in no uncertain terms, “I’ve earned this.” But what pray tell is it that he has earned? What gems stud the death mask of Scrutopia’s king?

But perhaps there is no need to disquiet the soul of Scruton. Perhaps in his writing he already has given up his secret in plain sight. In his book, A Political Philosophy, the conservative philosopher par excellence writes, “Conservatism is itself a modernism, and in this lies the secret of its success.”

As with Scruton, so the Scruton Café.6

Notes

Rather than refer you to authoritative literature regarding how Hungary is a beacon to the world, a shining cathedral on a hill, the hope of the Republican Party, and so on—I’d encourage you to take a moment to visit the Hungarian Folk Tales YouTube channel, which hosts a series of of animated Hungarian folk tales, which are all delightful. (I have watched them all.)

The other night while discussing Scruton’s equestrian activities, I was informed by a member of the greater DC-area foxhunting community (who shall remain nameless) that he had heard from a friend of a friend (who of course shall also remain nameless) that Scruton, who’d only properly become involved in foxhunting later in life, was actually a somewhat clumsy rider and often preferred to ride a pony—things I found very humanizing and moreover endearing given that they remind me of myself.

Apropos of nothing, I am 29 and will be monetizing this Substack in the near future.

Adam Smith once remarked that Burke was “the only man I ever knew who thinks on economic subjects exactly as I do, without any previous communications having passed between us.”

My own essay written in the wake of Scruton’s passing, “The Art of Madness and Mystery,” which touches on his aesthetics and legacy, is on the exact opposite side of the poignancy spectrum.

If you’ve made it here, I assume you are unsatisfied. Perhaps you would have liked more—or just a better ending. Perhaps you think that what I have said of the secret of the Scruton Café is a pseudointellectual cop out in the very worst taste. Perhaps you even suspect that I secretly think Scruton is a hack. To the contrary, let me reassure you that I really do admire him, though I cannot quite put into words why—certainly not to an extent that would give a real impression of the vastness of my admiration. Instead, allow me to recommend this performance of his Lorca Songs, which was recorded not too long before his death on a pleasant summer evening in Scrutopia.

Very nice. I've read quite a bit of Scruton myself. I liked his essay on oikophobia but couldn't finish the one on beauty. I don't think he was a race realist but I could be wrong.

About Oikophobia. I started the entry at Wikipedia. The following and a lot more were taken down. A small part:

An extreme and immoderate aversion to the sacred and the thwarting of the connection of the sacred to the culture of the West appears to be the underlying motif of oikophobia; and not the substitution of the culture by another coherent system of belief. The paradox of the oikophobe seems to be that any opposition directed at the theological and cultural tradition of the West is to be encouraged even if it is "significantly more parochial, exclusivist, patriarchal, and ethnocentric". (Mark Dooley, Roger Scruton: Philosopher on Dover Beach (Continuum 2009), p. 78.)

Scruton defines it as "the repudiation of inheritance and home," and refers to it as "a stage through which the adolescent mind normally passes." Roger Scruton, ''A Political Philosophy'', p. 24.

Excellent read, see you in Budapest!